This word study was written for an English class at SJSU.

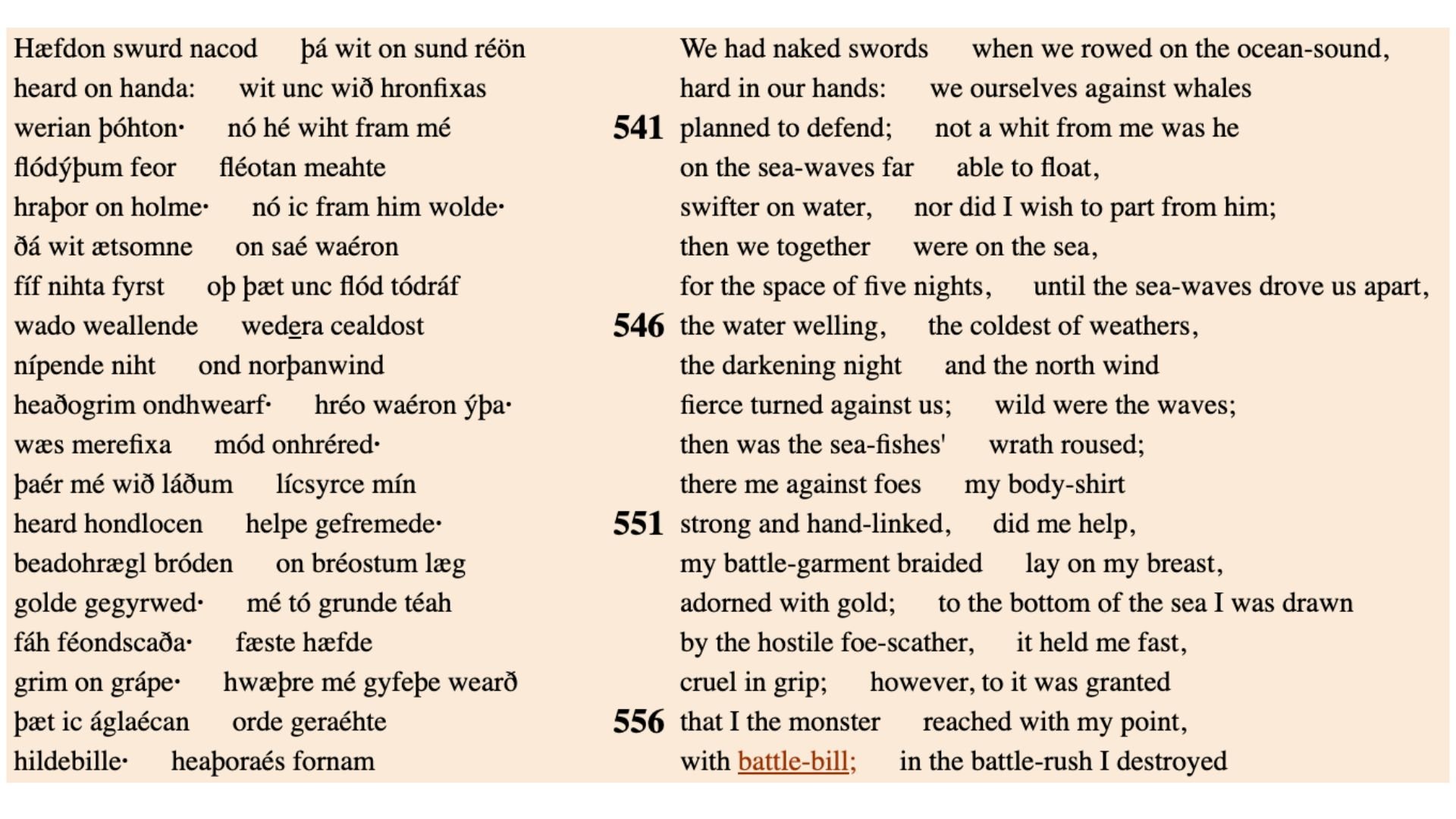

Beowulf is an Old English epic poem written approximately between the 8th and 11th century. Consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines, the poem chronicles the adventures of the Germanic hero Beowulf and his violent conquests over armies and monsters. Beowulf is considered to be one of the most important and well known works of Anglo Saxon literature, and continues to be one of the most translated texts of all time. The poem incorporates many different chronological and historical narrative timelines throughout, often told through character dialogue, and mainly expressed through the use of dramatic monologues. One such memorable monologue occurs upon Beowulf’s arrival to Heorot, a royal mead hall, where he and his army of Geats are invited by the Danish lord Hrothgar to drink and socialize. In the hall, Beowulf vows to destroy the creature Grendel, who has terrorized and slaughtered the hall’s inhabitants. After swearing to defend Heorot, Beowulf is then taunted by Unferth, a drunk and jealous thegn of Hrothgar, who claims that Beowulf lost a swimming match with his childhood friend Breca, when both men swam out into the icy ocean and stayed for seven nights, with Breca finally besting Beowulf after making it ashore first. Unferth publicly questions Beowulf’s ability to defeat Grendel when he can’t even win a swimming match between boyhood friends. Unperturbed by Unferth’s personal attack, Beowulf calmly and confidently recounts his harrowing oceanic experience in a fantastic monologue that offers an Anglo Saxon exploration of various aquatic sea-monsters. Benjamin Slade’s 2012 diacritically-marked text and facing translation offers an accurate and expert rendering of Beowulf’s tale:

All told, Beowulf claims to have killed nine sea monsters during the seven nights spent swimming in the Northern ocean, while wearing full armor and carrying only a “naked sword.” Within this monologue excerpt alone, the reader encounters the vivid descriptions of five marine creatures: “Whales; Sea-fishes; Hostile foe-scather; Monster; and Mighty sea-beast” are all words that Slade has translated from the original Old English text. By examining all five terms and referencing the Bosworth Toller Anglo Saxon Dictionary, as well as breaking down many of the words into smaller linguistic components, we can gain a deeper grasp on the language and definitions behind these underwater monsters.

The Anglo Saxon word “hronfixas” is the plural of the kenning (or Old English cognate) “hran-fisc,” which translates literally as “whales.” Once separated into two words, one can immediately connect the word “fisc” to the modern English word “fish.” The word “fisc” appears again in the next term, “merefixa,” a plural of the Anglo Saxon kenning “mere-fisc,” or “sea-fish.” This cognate of “mere-fisc,” when broken up, is again quite familiar and easily recognizable from a linguistic standpoint. Those with any knowledge of the Latin romance languages can see the commonality between the word “mere” and the Latin word for sea: in Spanish, the word for sea is “mar;” in French, it’s “mer;” in Italian, the word is “mare.” This word is an occurrence of an Indo-European cognate: while the language of the text in Beowulf is Germanic, many of the word roots throughout are derived from a much wider range of Indo-European languages. With this root, the Indo-European cognate of “mere-fisc” in Beowulf draws the Old English text linguistically closer to modern language.

The next phrase, translated by Slade as “Hostile foe-scather” is a bit more ambiguous at first glance. The Anglo Saxon term used in the text is “fáh féondscaða.” The Bosworth Toller dictionary of Old English provides multiple meanings to the term “fáh:” the first adjective defines it as “colored; tinctured,” while the second definition of “criminal, inimical, and hostile” is clearly where Slade settled on the word for his translation. The use of the letter “ð,” in “féondscaða,” also known as “ðæt” in Old and Middle English, is foreign to modern English. The capital letter of “ð” is “Ð,” which looks more like a capital letter “D” in the Western alphabet—however, the pronunciation of the letter Ð (and ð) is actually a “th” sound, as in the words “this” and “the.” Bosworth Toller devides up “feóndsceaða” into the kenning “feónd-sceaða,” translating “feónd” to “a fiend, foe, or dire enemy.” Again, we’re able to see a definite similarity between “feónd” and “fiend;” and while perhaps “fiend” is the closer word cognate, Slade’s use of “foe” is not far from the root; it is indeed part of the definition. “Sceaða” is connected to the modern verb “scathe,” which makes the “th” use of the letter “ð” quite understandable. Much like the previous terms, by breaking down “feóndsceaða” into a kenning, we can find familiar roots that give us insight into where the term “hostile foe-scather” derives from. It’s an excellent translation by Benjamin Slade that brings us as close to the original text as possible.

The use of the word “monster” in the text is the translation of “áglaécan,” which Bosworth Toller defines as “a miserable being; wretch; miscreant; monster; fierce combatant.” Again, Slade renders a sharply accurate interpretation of the Anglo Saxon text. The final term “mihtig meredéor” translates to “Mighty sea-beast” in Slade’s translation. Immediately we can see the similar spelling between “mihtig” and “mighty.” Turning “meredéor” in the kenning “mere-déor” brings us once again in contact with the word “mere,” for “sea.” The word “déor” has survived into the modern English word “deer”—but interestingly, the Anglo Saxon word “déor” was used in a much more general way, meaning (according to Bosworth Toller) “an animal, any sort of wild animal, a wild beast.” Centuries later, the word would be narrowed down in specificity to just one particular species of animal. But again, Slade’s translation of “mihtig meredéor” to “mighty sea-beast” is about as accurate as one can get to the original material.

For some readers, it’s easy to look at Old English texts like Beowulf and see it as a dead foreign language that holds little to no resemblance or significance to modern day English. But by isolating certain terms from the text, breaking them down into their linguistic components, and then examining their meaning piece by piece, we can start to see myriad language connections that have brought us to the present day. It can be an illuminating process; one that brings readers closer to the text, and helps deepen the relevance of the reading. It can be a gratifying experience to recognize that these epic texts from centuries ago are much more familiar to us than we may at first realize.